Embracing the artistic landscape of the 20th and 21st centuries, as J. Jouannais attempts to, necessarily obliges to converse with the vocabulary of the Avant-Garde which has constructed its horizon.

Embracing the artistic landscape of the 20th and 21st centuries, as J. Jouannais attempts to, necessarily obliges to converse with the vocabulary of the Avant-Garde which has constructed its horizon.

Functioning as the counter form of the Utopian scent that has enveloped the two world wars, the end of the 20thcentury witnesses the emergence of political, economic and artistic stands that resist to messianic belief in humanity’s progress, working instead on building the wall of disillusion. Sleek approaches emerge in a melancholic mode, stripped of any psychology of depths, as of any spiritual or mystic appeal. A time that will give birth to strictly materialist and individualised statements valorising technical process and pure conceptual stake. The Minimal artists, leading figures of these artistic positions, synthesise this inscription in the concreteness of materials and production protocols. One easily understands that such a distancing from effects of charm and uncertainty have, first, brought the Minimal artists to move away from Matisse’s discoveries relative to decorative questions. More than ever, taut between useless artifice and hypnotic strength, capable of generating an active void to the limits of optic trance, the decorative – being that, trans-Baroque, constricted by a Matisse – was first respected.

In the same spirit of radicalism, returning to a Dadaist posture attacking the object-artwork, the Minimalists mean to deconstruct the idealist and timeless definition of art which, even when it is considered as a criticism of consumer society, always ends in generating artworks to sell. Their critic hinges on the Classical approach according to which the work would always be an entity that conjugates a visible exterior and a psychological or sacred, mysterious and attractive interiority.

All their project will consist in systematically opening the work, in such a way to destitute the illusion of interiority, in order to only consider it from its strictly formal exteriorised procedures.

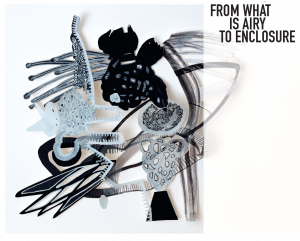

At the origins of the reversal that will unexpectedly create a convergence between Minimalist austerity and revisited decorativeness, we can initiate an observation : when the Minimalists appear on the scene, it is to ask themselves questions in the fields of sculpture or architecture close to those asked by Matisse. From the mechanic figures of the Endless Columnby Brancusi, or of the Large Glassby Duchamp, it is a question of inventing a way out of the dead end inherited by Classical sculpture, that affirms a hierarchy between plinth and figure, or between construction and moving emptiness. The depreciation of the plinth or of negative space reenacting, in this context, Matisse’s questions around the depreciation of backgrounds… Minimalist experiments will often bet on a equalhybridization of plinth and figure, either with the in situ inscription in the architectural context of the exhibition or of the landscape, either by the underlining of a homogeneity of production protocols between figure and plinth, either again by a staging of disjointed or consistent materials. However, in any case, it will always be a question of shattering the obliged reference to the object-masterpiece, it being figure, ready made, pop, recycled or tinkered. We here find the implicit part of J. Jouannais’s sculptural approach, as it immediately appears, from the first encounter, conflicting firmly, with strain, against the constitution of sculpture into object. Whether they be masses, lines or colours, whether they be effects of gravity or suspension, whether they be articulations of positive and negative space, all the profound energy of the works of J. Jouannais forbids the viewer-visitor to recognise an object. No use, no figure, no memory is ever identifiable. Yet to be understood, precisely, is what these shapes manage to however capture, as an unusual crystallisation …

By placing these projects in the light of the monad-facade deciphering of the work by Deleuze, we find the anchoring point that enables J. Jouannais to stretch between Matisse and Minimalism.

Even more so, it is by her side that I insist in reading Sol Lewitt’s production protocols, for example, a work framing the vacant part of an architectural site, misrepresenting with a controlled line the ungraspable spatial volume. The slack felt works by Robert Morris are also related to the decorative facade; their sole textured surface tries to sustain itself, deprived of an internal framework. The precarious installations by R. Serra, also constantly underlining the informal zone of space, however loudly affirm the industrial memory of material, as well as the shaking, through the creation of precarious balance, of any eternal or timeless dimension.

Indeed, everything happens as if, with successive experiments, the stake of Minimal artworks finally amounted to make itself a pure art of facade, that would have absorbed monad to the point of dissolving it in material and protocol.

Pure exteriorities, sheets of felt, steel plates, copper tiles, create the ambiguity of a membrane that reduces the fold to a strict unfolding, expansion of the texture-facade, manifestation of the exteriority of surface.

Whether being by D.Judd, C. André, R. Serra or R. Morris, all approaches seem to stretch the works towards exteriority, as if the question was to invert them like gloves. As testifies the famous list-manifest by R. Serra, the inventory of forms of sculpture is finally lowered to its operational modes : “roll, pleat, fold, curve, shorten, bend, mottle, burr, tear, split, cut, section, release, catch…”. Many verbs that base the work on pure procedure, that is pure exteriority, pure concrete implantation… In short, pure facade. Similar to a dance, the production protocol resumes itself to a variation of passes, of gestural figures that reenact the choreography of origins in a Grapho-Chore inscribed in material mass. One can recognise in the works of J. Jouannais the metamorphosis of these experimentations, that gave birth to a monumental, radical sculptural scene, sometimes pushed towards exteriority to the point of complete collision with landscape. Here, however, making openly hers the filter of a revisited decorativeness, the production procedures mute, generating a human scaled world : result of the body’s projection in mass and of its repercussion in the mind of the visitor-viewer

Evidently, the parallels between decorativeness according to Matisse, Deleuze’s trans-historical Baroque, and Minimalism, are bold. It is precisely this boldness that I find important to underline, in order to render the extent of J. Jouannais’s gesture, by replacing it in the field of contemporary interrogations. Indeed, under the appearance ofcasualness and modesty, it is important to take notice of this brave and innovative transplant she carries out. By restating the Minimal critique of the masterpiece, which affirms the identity of art in these procedures, J. Jouannais restages the inversion of the artwork to its pure exterior, freeing itself from any idealism. Like the leading figures of Minimal art, she averts from any effect of fascination, emptying the work of its mysterious side, preferring shadow to glare in the visible completeness. She however takes care to never totally make hers the affirmation of sole facade, which has sometimes confined Minimalism to a hieratic, sometimes almost tyrannic stiffness. On the contrary, stitching a decorative and pleasurable line on the facade work, bringing back the work to the body’s scale, she joins the field of disobedience, of the fluidity of desire. The decorative stake then reveals itself in all its transgression and subversion, open to the unlimited reinvention of the dance of bodies. Which, by an appealing and typically Baroque inversion, is the best way to make the work ungraspable, or evenunfit for consumption.

Evidently, the parallels between decorativeness according to Matisse, Deleuze’s trans-historical Baroque, and Minimalism, are bold. It is precisely this boldness that I find important to underline, in order to render the extent of J. Jouannais’s gesture, by replacing it in the field of contemporary interrogations. Indeed, under the appearance ofcasualness and modesty, it is important to take notice of this brave and innovative transplant she carries out. By restating the Minimal critique of the masterpiece, which affirms the identity of art in these procedures, J. Jouannais restages the inversion of the artwork to its pure exterior, freeing itself from any idealism. Like the leading figures of Minimal art, she averts from any effect of fascination, emptying the work of its mysterious side, preferring shadow to glare in the visible completeness. She however takes care to never totally make hers the affirmation of sole facade, which has sometimes confined Minimalism to a hieratic, sometimes almost tyrannic stiffness. On the contrary, stitching a decorative and pleasurable line on the facade work, bringing back the work to the body’s scale, she joins the field of disobedience, of the fluidity of desire. The decorative stake then reveals itself in all its transgression and subversion, open to the unlimited reinvention of the dance of bodies. Which, by an appealing and typically Baroque inversion, is the best way to make the work ungraspable, or evenunfit for consumption.